The Beautiful Mind of Lewis Nkosi

By Phakama Mbonambi

When veteran South African writer Lewis Nkosi fell and banged his head on a pavement in Melville, Johannesburg, more than a year ago, it was the beginning of the end of a colourful and controversial life. The tragic fall, his second following a drunken binge in this bohemian enclave of Johannesburg, saw him confined to hospital for about a year, with doctors desperately trying to save the life of this literary genius, who gave the world such masterpieces as Home and Exile and Mating Birds. Brain scans indicated internal bleeding. There was a succession of strokes. He was variously at Helen Joseph and Charlotte Maxeke hospitals as well as at Park Care hospice.

His partner of many years, Astrid Starck-Adler, flew in from Switzerland to be by his bedside. So did his twin daughters Joy and Louise, from Britain.

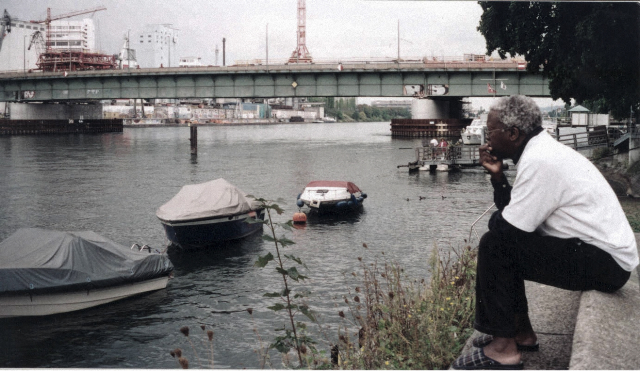

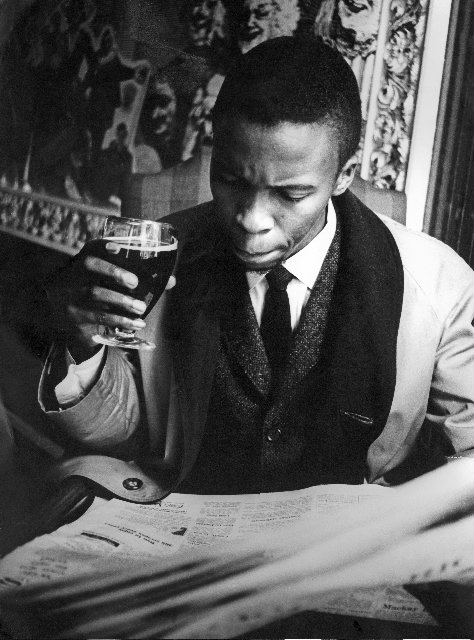

No doubt, as they held his hand, they remembered Nkosi as he once was – a dashing man in a fedora or a jaunty, Trotsky-style cap, a bohemian intellectual, a loving father, a fearless literary critic, an inspiration to lovers of literature.

“Until the end, even though he could hardly speak, he was grateful to those who visited him and asked them to come again,” says Starck-Adler. “He had a strong will to live, though he was very ill.”

But, slowly, his body and memory withered away.

The end came in the early hours of September 5 last year. He was seventy-three. His resting place was at Stellawood Cemetery in Durban.

Nkosi’s world

Booze felled Nkosi, but there is no denying that he inhabited the literary world – and his own life – as only few could. Because he spoke his mind, Nkosi divided opinion. For example, he fervently believed that black writing, apart from vilifying apartheid, must be really polished before it could be labelled serious literature. For that view, he was crucified for years.

“He did not suffer fools gladly and hated ‘triumphalist’ and ‘nationalistic’ propagation of literature and other arts that lacked sincerity and theoretical vigour,” says Sandile Ngidi, Nkosi’s local agent for his last book, Mandela’s Ego. “He had an immense understanding of literature as a craft and an expression of a people’s experience.”

Being an anarchist, Nkosi lived according to his own rules. “Lewis did not observe any boundaries in connection with anything in life,” says Prof Willie Kgositsile, the national poet laureate. The two met when they were young journalists in Johannesburg, Nkosi with Drum and Kgositsile with New Age.

“Lewis didn’t believe that laws had to govern human behaviour. He just wanted people to live and do as they pleased … He was also reckless. Even if he was talking to a crazy clown who could potentially beat him up for asking a question or making a comment, Lewis would still go ahead and ask a question or comment. He never cared about the consequences,” Kgositsile recalls.

To read the rest of this article, get a copy of Wordsetc for R69.95 or subscribe to Wordsetc for a special offer price of R223.84 for four editions and stand a chance of winning fantastic book giveaways (this special offer is valid until end of May 2011).

For enquiries, write to [email protected]

Facebook comments: